Implications of the ISCA 2.0 GI Metrics

Implications of the ISCA 2.0 GI metrics

By Dr Martina Girvan (Arcadis, UK)

Dr Martina Girvan was an international speaker at ISCA’s 2018 Annual Conference. Martina is a Chartered Ecologist with over 20 years’ experience in the UK. The integration of biodiversity with society is a lifelong passion, she is currently developing the Natural Capital approach within Arcadis to ensure that their projects deliver benefits for biodiversity and business.

I was delighted to be invited by the Infrastructure Sustainability Council of Australia (ISCA) to present and participate in the discussions around the integration of Green Infrastructure (GI) into their sustainable infrastructure metrics at the 2018 ISCA Conference in Sydney.

Green Infrastructure is also called living infrastructure and it is comprised of plants, soil and water that have a functional role in our built environments. Examples of these GI elements are green roofs, living walls, rain gardens, pocket parks and street trees. You may also hear the terms Green Blue Infrastructure, Water Sensitive Urban Design (WSUD), Sustainable Drainage Solutions (SuDS) and Biodiversity Sensitive Urban Design (BSUD) used in the context of GI.

- Green Infrastructure (includes Blue (water) and Brown (soil) elements), unlike Grey Infrastructure, is multifunctional in terms of benefits and as a living infrastructure can respond to change and provide resilience. These benefits are often termed Ecosystem Services. The urban benefits include:

- Improving health and wellbeing; by encouraging an active population that engages with nature for improvements in both physical and mental health;

- Providing water management; GI can hold onto storm water to reduce or prevent flooding but also filter that water to minimise pollution;

- Amenity, recreational and tourism benefits; by providing attractive environments that people want to spend time in;

- Providing cleaner air; as air quality issues continue to impact upon health primarily due to burning of fossil fuels and the particulate matter in the atmosphere, localised air quality improvements from GI, by removal of particulate matter from the air can benefit health, including improved mental development in children; and

- Supporting and maintaining biodiversity; it may be surprising to learn that, according to an article in Global Ecology and Biogeography , the average Australian City is home to 32 threatened species (supported in gardens, public open spaces and other building integrated GI). This is three times as many threatened species per unit area as rural environments so GI has a vital role to play in maintaining their populations.

Green Infrastructure can also often cost less than Grey Infrastructure to install and maintain so over the life cycle of a development, GI elements can actually deliver a return on investment.

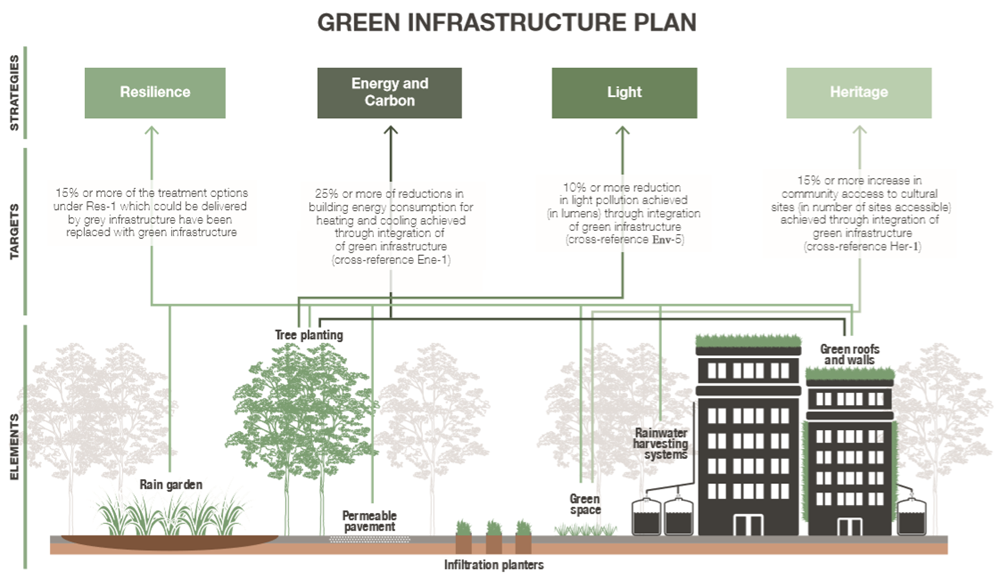

The launch of the IS version 2.0 Green Infrastructure category in Australia (similar to CEEQUAL in the UK) includes GI for the first time and so presents an opportunity to implement GI more widely than ever in built infrastructure. ISCA recognise the importance of capturing GI’s functionality for the resilience of our built environment via the Ecosystem Services they deliver (Image below). The metrics reinforce the importance of maximising the synergies GI has with other IS credits such as Resilience, Energy and Carbon, Heritage and Ecology to name a few. This is achieved by linking the GI elements with the other credits and providing appropriate targets for those credit categories. For example, by integrating green roofs and walls one could set an energy usage reduction target, due to passive summer cooling and winter insulation. It is a truly holistic and multidisciplinary approach which will facilitate interaction between the many disciplines (biodiversity, civil engineering, water designers, air quality, noise, cost consultancy etc.) to take advantage of opportunities and maximise efficiencies. The approach has the potential to produce a better design which delivers more benefits to the public at minimal additional cost.

As the global lead for driving the integration of the Natural Capital approach into Arcadis design and consultancy work, I was grateful for the opportunity to share my experiences of delivering GI and Natural Capital design strategies with the ISCA Conference audience. I was also able to share a case study for the Arcadis designed North West Bicester Eco-Town that will deliver 6000 homes on a greenfield site to the north of Oxford. In addition to delivering 40% net gain, we calculated the benefits of the GI at around £780 per annum, per home (based on an assessment of 393 homes on the exemplar site), delivering tangible benefits both to business and the wider public.

This presentation was followed by a panel discussion facilitated by Adam Beck from the Smart Cities Council. The panel companions were Professor Barbara Norman, author and Professor of Urban and Regional Planning, University of Canberra (who recently received the ACT Planning Award for Cutting Edge Research and Teaching), Lisa McLean CEO of the Open Cities Alliance and Tim Watson from Edge sustainability consulting. Adam challenged the panel to consider “do we know whether our cities are sustainable or not.” The panel was in unanimous agreement that while we have indicators such as the sustainable cities index, more quantitative information on performance would be useful. However, it is clear that action is needed and needed now.

Our cities are not sustainable, nor are our communities. Lisa was clear that the influence of local people was significant with the change in philosophy towards prosumers as opposed to consumers. This can be very powerful and will pay a big part in driving cities to deliver a different model of energy, transport and water supply. Barbara advocated for the refocus and re-empowerment of planners to ensure GI is integrated into design. The barriers to implementing GI were agreed to be around the perceived risk around the loss of developable areas, effective design and the cost of maintenance. I reinforced that the value of the benefits GI bring far outweigh their capital and operational costs and compare much more favourably to that of Grey Infrastructure, it’s just that different funding models are required. Using tools such as the CIRIA Benefits of SuDS Tool (BEST) or a bespoke Natural Capital assessment, one can actually monetise the benefits of GI. This can be used to contribute to private/public funding mechanisms as well as stakeholder engagement to ensure successful implementation of those mechanisms.

Whilst further research would be beneficial, it appears that there are benefits from GI maintenance, maintaining green assets provides healthy, stimulating jobs that are in many ways more attractive and less onerous than Grey Infrastructure maintenance. Tim was encouraged by Melbourne’s recent efforts of greening the city and its delivery plans. He discussed how if Melbourne realises the value in GI it could make the city more attractive and therefore more competitive in the tourist, retail and recreation markets.

Melbourne is actually building their own 2 mile long elevated Skypark, linking Federation Square to Southern Cross Station which will provide a high profile piece of multifunctional GI. An idea inspired by the High Line, a great example of the successful integration of GI into a city. High Line is a 1.45 mile long elevated linear park, greenway and rail trail created on a former New York Central Railroad spur on the west side of Manhattan in New York City. Since opening in 2009, the High Line has become an icon of contemporary landscape architecture. The project has spurred real estate development in adjacent neighbourhoods, increasing real-estate values and property prices along the route. As of 2017, the park had seven million visitors annually. The High Line is a public park programmed, maintained, and operated by Friends of the High Line, in partnership with the New York City Department of Parks & Recreation.

To summarise, within a city GI can play a large part in delivering climate, social and economic resilience. Climate resilience through storm water management, passive cooling and insulation, waste water purification and soil stabilisation. Social resilience by providing better air quality, increased biodiversity and amenity to provide a more attractive environment to encourage greater mobility in residents promoting health. There is also clear evidence that interaction with quality GI improves mental wellbeing. Economic resilience is delivered through greater recreational opportunities and retail footfall and attracting people to visit and stay in the city. There are however barriers to implementing GI, usually due to potential loss of developable space and concerns over effective design and maintenance costs.

By providing the framework for infrastructure engineers to identify and capture GI benefits more tangibly, the ISCA GI metrics have provided a platform for multidisciplinary collaboration to maximise the value of a development. They are aligned to the world Sustainable Development Goals and by incorporating the functionality of GI put Australian infrastructure projects at the forefront of sustainable thinking.

With these benefits, the future will not only see new developments that include quality GI as standard but should also result in existing developments being retrofitted due to the business benefits from the added value. In addition, this approach could spread throughout the commercial and public sectors, making development and management of land portfolios more resilient and productive without degradation. Australia has the opportunity to use this period of enormous capital expenditure to integrate climate resilience, maximise economic values and secure environmental benefits for future generations.