An Innovative Approach To Provide Emergency Water For 400,000 People

Challenging tradition. An innovative approach to provide emergency water for 400,000 people

This article is taken from ISCA’s 2018 Impacts Report.

Cardno NZ’s Technical Director of Infrastructure Strategy Antony Cameron gives a 101 on water supply resilience.

More people, more frequent climate extremes. Modern infrastructure is under pressure to perform, but funding for infrastructure upgrades and renewals is stretched. Water infrastructure is one of many groups completing for funding to meet these challenges, especially in the emerging field of disaster resilience.

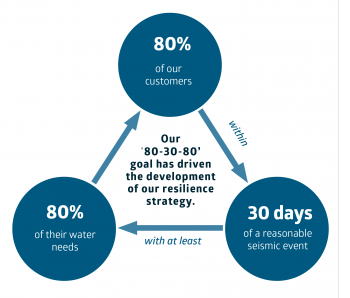

Access to sufficient quantities of fresh water is also a key ingredient in preventing major outbreaks of disease following a significant disaster. The Wellington region is not alone in sharing competing infrastructure challenges. Driven by a global need to develop smarter outcomes against the backdrop of financial and time based constraints, Cardno decided to challenge traditional resilience thinking. This led to the development of a low-cost, twelve-month water resilience strategy that has achieved a major step change in levels of service for more than 400,000 residents in the Wellington Region.

Continuous improvement of water services through latter parts of the 20th century has led to both complacency that water will always be available, and complete dependability on emergency services to provide an alternative when it isn’t. This dependability is the Achilles Heel for many communities where few or no alternatives exist to the normal reticulated water supply. Problems are exacerbated in Wellington where water treatment plants are located significant distances from major urban centres. In-between lies hundreds of kilometres of pipeline, susceptible to many natural hazards including landslides, liquefaction, fault rupture and urban debris.

How long should communities be prepared to wait for basic water services?

“The typical approach to water supply resilience in many cities is one of ‘we must be there in the event of a disaster.’ The problem with this approach is people fundamentally dislike being let down, especially when we’re talking critical infrastructure”, says Antony Cameron, Cardno NZ’s Technical Director of Infrastructure Strategy. “We decided to approach things differently. What if we communicated pragmatically? And said ‘we can’t, and won’t be there in the event of a disaster.’”

Cardno turned to the use of leading cellular analytics to understand how people moved in and around the region based on real cellular data. This data helped confirm that the lack of transport across the region would effectively create 17 miniature ‘islands’ until these transport routes were restored. The team further found that people may be walking home for up to four days.

This information was a key to informing the community-centric approach of the Community Infrastructure Resilience Programme. “The data told us we can’t be there, and even if we could the response may be patchy. This was a key foundation in our community-centric approach,” says Antony. “We recognised we needed to empower communities with resilient water services within each island, while also planning for a utility-led response”.

This led to the first phase of resilience work to investigate and establish water sources in each island. Cardno first completed extensive hydrogeological investigations into the regions ground and surface water. We were targeting a service level objective of providing 20 litres of water for every person, every day, within 1,000 metres of every Wellington home. This meant we needed to identify around 22 new water sources each capable of producing water at a rate of roughly 350,000 litres per day.

Once suitable water sources had been identified, Cardno worked with local suppliers to design and build 22 containerised water treatment systems called “Community Water Stations”. Each system is self-contained, sitting in hibernation at the site, awaiting rapid setup following a significant earthquake. Each unit can also be transported around the region to support other areas if it is not required at its own site.

The final piece of the puzzle involved procuring over 400 water bladders for transport and storage of water after an earthquake. These water bladders are normally stored in water stations or around islands, each about the size of a large rolled up sleeping bag. Their small size and light weight make them ideal for emergency applications. The bladders will be accessed after the event and filled with water from reservoirs and water stations, creating an ‘above ground’ mobile water network. They form an integral part of the requirement to provide water within 1,000 metres of every Wellington home.

How does this empower communities?

Normal infrastructure services will cease operation for an extended period of time following a significant earthquake so the community will naturally turn to local alternatives. The combination of assets and integrated emergency planning delivered by Cardno provides communities with the tools and information they need to get by, with or without emergency services.

Together, these communities can access existing water reservoirs as well as work with limited emergency services to open and operate Community Water Stations. This means that each island is able to provide the 20 litres per person of water needed to get through the emergency. The community will also access stored water bladders, unrolling them in vehicles such as trucks or utes, and filling them with water. These vehicles are then used like a water tanker, transporting water to larger stationary water bladders that are set up around each community. Water mobility also means the community can adapt to specific needs; maybe a rest home or medical facility needs water which it would otherwise be unable to access.

Cardno’s innovative approach to resilience challenged the way cities can deliver high-value, low-cost, resilient infrastructure against the backdrop of many emerging infrastructure challenges. No matter the size of the earthquake, and no matter the location, each community within 17 ‘islands’ can access tools and maintain emergency water supplies until network services are restored to homes around the region.